There Is a Lot More in Him Than You Guess...

A couple of months ago, I asked my students what the word education means. They were nearly unanimous in their responses. “Education means learning.” Partially correct, but there’s more. I told them that they are getting an education, so it might be beneficial for them to know what the word means.

The word education comes from the Latin word, educere, which means to lead out. And of course, the implication derived from “lead out” is to lead out from something to something. Andrew Zwerneman of the Cana Academy described this as “leading students out of ignorance and out of the limits of their immediate world.” When students are being properly educated, the eyes of their souls are being opened. They are being led out from blindness to sight, from darkness to light. (The image of Plato’s cave certainly comes to mind here!)

Fundamentally, education really is about seeing. The responsible educator, taking an inventory of his or her students, might therefore be asking questions such as…

Do my students see truth, goodness, and beauty?

Do they see beyond themselves?

Do they see how things relate to each other, analogically, thereby illuminating their souls’ understanding that all things hold together in Christ, the Logos?

Do they see their own sin?

Do they see God?

How do my students see themselves?

How do they see each other?

How do they see a math problem, a science experiment, a Latin conjugation, the journey of a protagonist in a great book, a Rembrandt, a Mozart, etc.?

But I think there is an important question that must precede any consideration of these questions—one that I would argue is almost necessary to address before we can ever hope to respond to these questions in the way we would all hope to as educators. And that question is this: how do we see our students?

Let’s get into this by first talking about someone who saw—really well, in fact. I wonder if this quote gives him away: “There is a lot more in him than you guess, and a deal more than he has any idea of himself.”

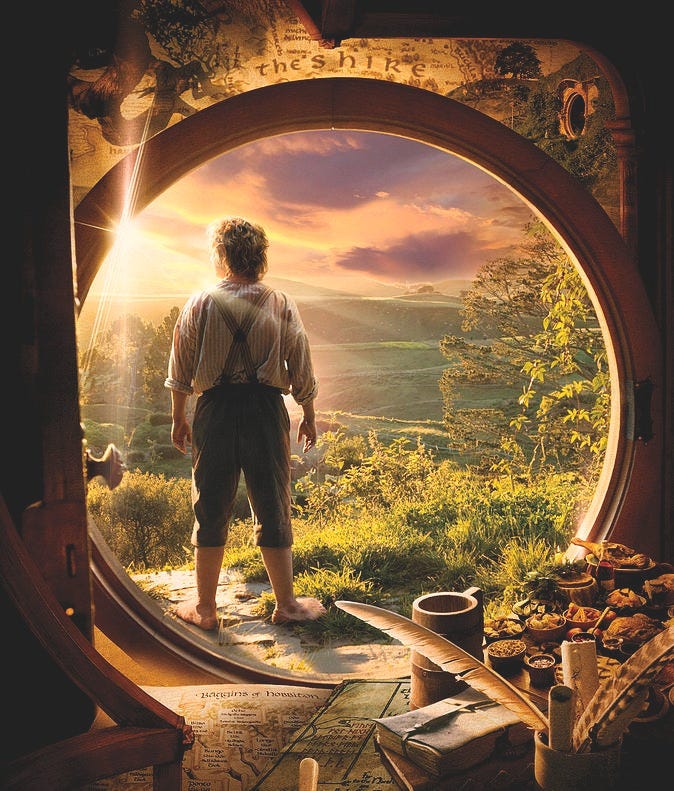

I will never forget the first time my eyes read these words of Gandalf in the first chapter of Tolkien’s The Hobbit. Gandalf’s two-part proclamation here reveals his determination to magnify the potential of Bilbo Baggins in the eyes of both the dwarves and Mr. Baggins himself. Gandalf perceived something in Bilbo, and in that moment, Bilbo and the dwarves were not capable of apprehending that truth spoken by Gandalf. To his newly found peers, and to himself, Bilbo was a gluttonous, comfortable, pleasure-seeking little hobbit. But Gandalf didn’t see that. Gandalf saw Bilbo. But Bilbo could not yet see Bilbo. He had to go on a journey; he had to undergo an education. He had to be led out from blindness to sight!

On the first day of school, my 6th grade literature students enter the classroom to notice this exact quotation written on the board. Before even opening the book jacket of The Hobbit, I confront each of my students with Gandalf’s quote, and I substitute each student’s name for Bilbo’s. The classroom proclamation is made; my students are individually advised that there is so much more to them than what they know and what their peers know about them.

I’ve taught 6th grade literature now for four years. Each year, my students have wondered the same thing: “Dr. Valley, how can you say that?” In other words, how was I so readily able to bestow the words of Gandalf upon them? Am I just being a really positive person who thinks the best of my students? Maybe, or maybe there is something more to it. Maybe truth flows from such a proclamation.

Before becoming a classical Christian educator, I was an occupational therapist, or OT for short. As an OT, I often worked with stroke survivors who were suffering from hemiparesis, or weakness on one side of the body. This impairment prevented them from effectively performing their daily activities. It was my job, as an OT, to aid them in returning to these daily activities. When working with clients who have had a stroke, a therapist can be tempted to implement therapeutic techniques that focus solely on the impairment, so for instance, prescribing arm exercises to facilitate motor return in the impaired arm. The client is therefore essentially reduced to an upper extremity impairment. This reduced perspective of the client is contradictory to the philosophy of OT, which advocates that clients are holistic beings who engage their entire selves into their daily activities.

Years back, I was assigned to a 65-year-old female who was two weeks post-stroke and had moderate hemiparesis on her right side. Now, I could have identified my patient as her impairment and worked on rehabbing her right arm. But instead, I chose to perceive my client as a lot more, even a deal more, than an impaired arm. She had told me that her favorite thing to do was make big spaghetti dinners for her family on Sunday, so that’s exactly what we did in therapy. At first, she didn’t think she could do it, but she ended up doing a fantastic job, using both hands to make the meal, and she loved every second of it.

If I were to have had a reductionistic view of my client, a pragmatic rehab approach would have targeted the limiting factors of my client that would have been prominent in my reduced view of her. I would have dismissed the holism of my client and reduced therapy to rehabilitating her impaired arm, and in doing so, I would have become master over her and assumed control over the outcome of her therapy. My client’s experience in the kitchen would have never occurred. In accordance with the philosophy of OT, I needed to see my client as a holistic being.

Now, of course, this is not an article on how to devise effective intervention plans for OT patients. So wherein lies the link between my vision of my client and the subsequent therapeutic intervention, and Gandalf’s proclamation and classical Christian education? Perhaps it could be argued that in the clinical scenario I just described, I was a sort of a “Gandalfian” therapist. I saw a deal more in my client than she saw in herself. Instead of leaving her in her hobbit hole (hospital room) to do meaningless exercises, I led her into an environment that reflected the joy and splendor of who she was. My client came to life through the execution of this therapeutic activity.

Thus, the connection must be made: in order for me, as a classical Christian educator, to help my students experience the fullness of who they are in their educational pursuits, I must first perceive them accurately. Herein lies the answer to the question I asked earlier: how was I so readily able to bestow the words of Gandalf upon my 6th grade lit students? Each of my students is a masterpiece created in the ineffable and inestimable image of God.

Now, please don’t misunderstand me. When I say “masterpiece,” I am in no way referring to some Rousseauian idea of a young one who is utterly innocent, or sinless, or inherently good. Not at all! I’m talking about a child, with all of his strengths and weaknesses, positive attributes and impurities, made in the image of God and precious in His sight. Theologian Joel Beeke identifies man as a “fallen masterpiece of God.” Or, consider how author and pastor, John Burke, puts it: seeing “the masterpiece hidden beneath the mud of sin.” I love what Andrew Kern mentioned in a lecture in which he was speaking about Jesus being around sinners. Kern asserted that Jesus was able to do this because He saw the image and the beauty of His Father on them.

Do we see the imago Dei on our students? Have we ever stopped to ask ourselves if we see on them the divine fingerprint? Akin to my OT experience with my stroke survivor, it can be tempting to reduce our students to their component parts: behaviors, grades, etc., or a combination thereof (to be discussed in a future article); however, such a reductionistic perception will inevitably lead to a reductionistic pedagogy. “The child needs to be fixed! And I’m the one to help him.” Yet if education is, in a sense, an opening of the eyes of the soul, with such a reductionistic perception of the student and corresponding pedagogy, what exactly is this student going to see? The answer(s) to this question in this particular circumstance ought to invoke fear and trembling.

Sure, we can ask the aforementioned listed questions about what our students see, but perhaps a better place to start is with ourselves. There is, indeed, a lot more in our students than we’d guess—so what then does this mean for us educators?

To be continued…